As the SCA’s 2019 Expo Portrait country and a place meaningful to us here at Atlas, we’re kicking off a series about Burundi—a heart-shaped country equivalent in size to the state of Maryland, with a population of 11 million, and physically wedged between Tanzania, DR Congo, and Rwanda. Over the next month we’ll cover a range of topics, including a brief history of Burundi and coffee, interviews with some of our producer and logistics partners, and roasting and brewing tips.

For the first post, let's dive into Burundi’s history. [As a warning, Burundi’s small physical size of a country belies its gruesome history, so the following several paragraphs may be difficult to read.]

Flag of Burundi. The three stars represent the three ethnic groups that live in the country (Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa). The red in the flag stands for the struggle for independence, the green for hope and the white for peace.

Historical Background

The Kingdom of Burundi (also known as the Kingdom of Urundi) was created in the early 17th century and was ruled by monarch. The king, with the title of Mwami, owned most of the land and required a tax from local farmers as he sought to expand his territory. European missionaries and explorers arrived in 1856, and from the late 19th century until its independence in 1962, Burundi was tossed around like a hot potato by different European entities, including Germany, Belgium, and the League of Nations. In 1899 Burundi became a part of German East Africa despite king Mwezi IV Gisabo’s efforts to resist European influence. In 1916, the Belgian military occupied the territory of Ruanda-Urundi (which included current-day Burundi), and in 1922 the League of Nations mandated the territory to Belgium.

A Pygmy people called the Twa are Burundi’s original inhabitants, but currently only make up ~1% of the population, with the majority of the population being divided between the Hutu (~80%) and Tutsi (~20%). Both Hutu and Tutsi speak the same language, share many cultural characteristics, with traditional differences being occupational: Hutu were often farmers, and Tutsi were considered elite cattle-owners. In 1933, Belgians exacerbated any tension by requiring everyone to carry an identity card indicating tribal ethnicity.

Several periods of drought in the early 1940s led to the Ruzagayura famine of 1943-44, which caused the estimated deaths of one-third to one-fifth of Burundi’s population, and a large migration of Burundians to neighboring Belgian Congo, where Belgium had been sending Burundian resources. Burundi achieved full independence from Belgium on July 1, 1962, inheriting an unstable political and economic climate.

Unfortunately, Burundi's troubles were far from over; in 1972, an estimated 300,000 Hutu were displaced, and another 200,000-300,000 were killed by government troops and the Tutsi ruling party in response to a Hutu rebellion. Burundi underwent a series of regimes, both bloodless and by coup-d’état.

In August 2000, a peace treaty called Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement (also known as the Arusha Accords) was signed in Arusha, Tanzania, starting the long process of ending Burundi’s Civil War. The Civil War started in 1993—after the country’s first democratically elected president was assassinated after only 100 days in office—and lasted until 2005. 2007-2014 saw a period of economic growth, but a political crisis ensued in 2015 when President Pierre Nkurunziza decided to run for a third presidential term (which violated the Arusha Accords).

Suffice it to say, Burundians have been through unthinkable atrocities, and through it all have been resilient, living daily life growing cash crops like coffee and tea while they try to forge forward with limited resources (In 2017 Burundi had the 2nd lowest GDP per capita according to the World Bank).

Coffee in Burundi

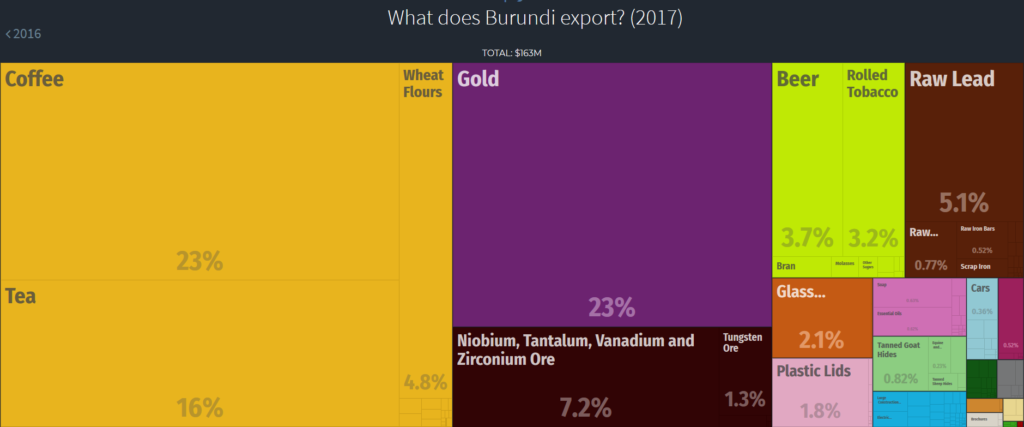

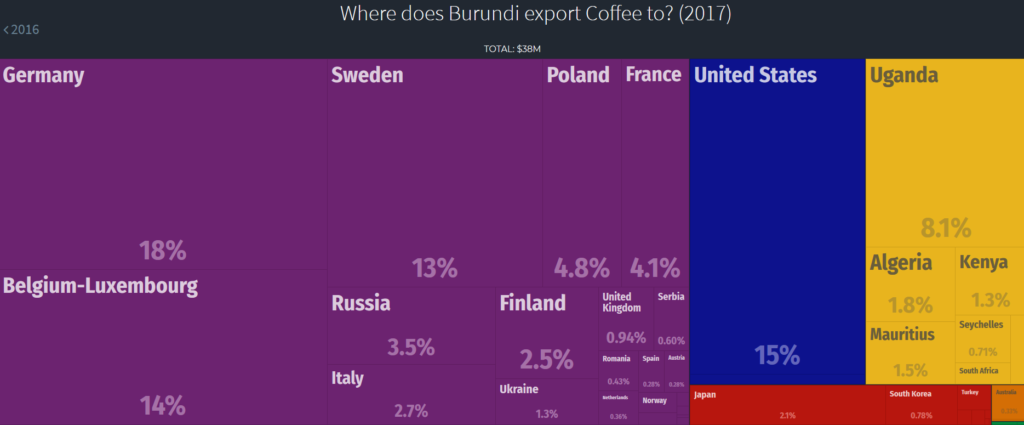

Today, coffee—and its success—is vital to Burundi’s economy. Coffee is its leading export, slightly edging out gold in terms of value, and an estimated 600,000-800,000 coffee farmers are involved in its production, with an average plot size of .12 hectares (think 110 feet square) and ~ 200 trees. If a smallholder farmer doesn’t own coffee trees, he or she knows someone who does.

Coffee was introduced to Burundi in the 1930s by the Belgians who had brought over Arabica coffee seedlings. After independence in 1962, the coffee sector was privately run for more than a decade, and the quality and quantity of coffee produced during that period slowly eroded due to the repeated political upheaval. The coffee sector was eventually taken over by the state in 1976, with mixed results, and from 1991 to 2008 the government set up an auction system. In 2008 the World Bank led the privatization of the coffee sector, making it possible for private companies and cooperatives to own washing stations and dry mills that had previously been owned by the state.

Currently, a minimum cherry price is set by the government to protect smallholder farmers, but when the coffee market is extremely low as it has been this past year, it can make it challenging for cooperatives, for example, to meet their overall cost of production. Still, progress is being made – a $55 million World Bank funded coffee project (Coffee Sector Competitiveness Support Project), which began in 2016, improved production by over 15% between 2016 and 2018 by giving farmers subsidies for fertilizer and insecticides, grants for bicycles, training, and motorcycles and vehicles to agronomists. Burundi’s topography, like neighboring Rwanda, is very hilly –great for coffee trees to thrive – with most coffee growing between 1,200-2,000 meters above sea level and harvest running from March to July.

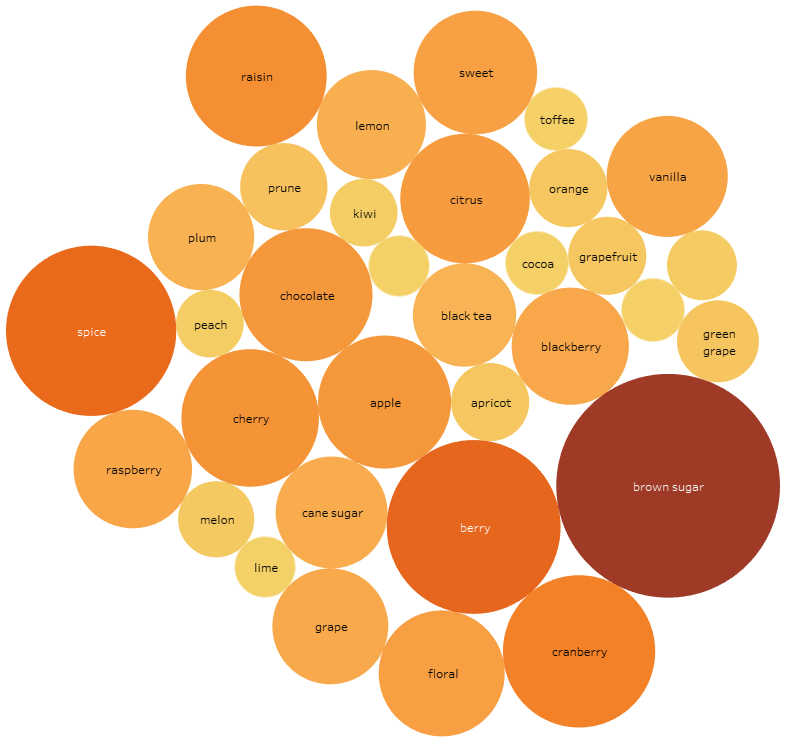

Burundi currently has around 283 washing stations and 8 dry mills throughout the country (both privately, and cooperatively owned), but concentrated in the Northern and Central provinces. Burundi’s washed-process coffees are also unique in that they are often “double fermented”/”double washed”, which results in an exceptionally clean and tasty cup. First cherry is floated in a bucket or concrete basin with underripe coffee aka “floaters” skimmed off; then it’s depulped and dry-fermented for 12-24 hours where it sits in a tank; followed by being washed n channels (with different quality coffees going into different tanks based on density); and finally then wet-fermented/soaked for another 12 hours before put on raised beds for sorting and drying for 10-20 days depending on weather. Coffees from Burundi are hard to beat, offering bright stone fruit notes, juicy acidity, and silky body, and each holiday season we look forward to arrivals from our Burundi partners.

Feel free to reach out to your sales rep for samples from our Kalico, Fairtrade COCOCA, and COPROCAME lots, and if you’re attending Expo, please come visit our Roaster Village table between 9-11am on Friday, April 12th and talk to Angele and Alex of Kalico, who own seven washing stations and are doing innovative work by promoting their “Kalico Mama” line of women-produced coffee.

Additional resources

Books: Novella “Small Country” by Gaël Faye and “Strength in What Remains” (non-fiction) by Tracey Kidder.

Website Resources: Café de Burundi: https://www.cafeduburundi.com

BBC Country Profile of Burundi: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13085064

Coffee Sector Competitiveness Support Project: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-12-27/burundi-counts-on-women-youth-pygmies-to-double-coffee-output