In January, Drew & Jen went to visit Bukonzo Joint Cooperative Union in Western Uganda for our Second Annual Cupping Competition and Cupper Training.

.

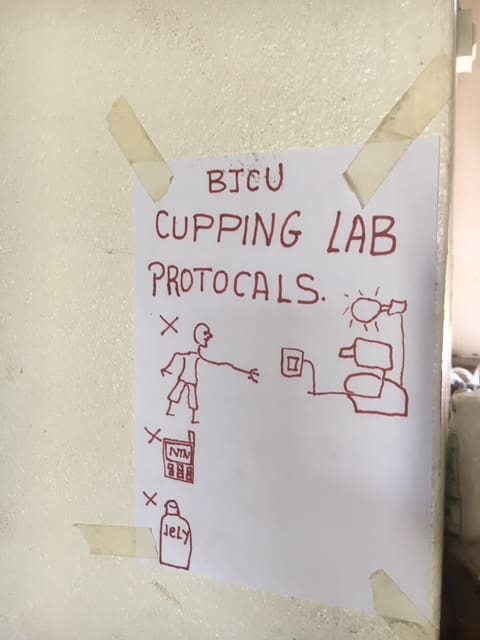

Our last trip there was in October of 2015, which was on the occasion of the inauguration of BJCU's brand new lab--built and equipped with money generously donated by an amazing and forward thinking group of their buyers. During the 2015 trip, Drew spent a week working with their Quality Team on Cupper Training. Three men and three women cooperative members received training on sample roasting, lab management, and basic cupping. Towards the end of the week, Jen and the buyers arrived for the Cupping Competition.

This year, one of the initial trainees had moved away, but the other five cuppers were all still working in the lab and were excited for additional education. We also invited representatives of Kawa Maber Cooperative from the Democratic Republic of Congo to travel to Kyarumba for the training. They are hoping to build their own lab in the future.

For this report, Jen & Drew ask each other questions about the trip! They have lots of good info to share so here's Part I of their Two Part Q&A series. Enjoy!

.

Drew: Jen, having traveled to Western Uganda many times now, you have a great perspective on the trajectory of specialty coffee in the region. Can you summarize for us some of the most significant changes you have seen over the past few years?

Jen: Great question, Drew! I joke about this sometimes, but it’s actually true: when I first started traveling to Western Uganda I said that I would be so happy to see specialty coffee be a repeatable quality produced there within my lifetime. In reality, we’ve seen that happen over the course of just a few years and I think it has everything to do with Bukonzo Joint essentially re-inventing the system.

For background, historically, this region has produced primarily natural-processed coffee, sold as Drugars (short for Dried Uganda Arabica) to commercial buyers at negative differentials. While there have been a number of valiant efforts—with varying degrees of success—to produce specialty naturals over the past few years, it is really challenging. The reasons are that you have an incredibly complex and well established supply chain with hundreds, even thousands of individual participants. Most coffee farmers own two hectares of land or less, and only a few hundred coffee trees. I did the math one time and if you divide the total production of the country by the number of farmers, the average is 6 bags of coffee per farmer. So, in order to do anything meaningful in terms of better picking or drying, you have to convince a lot of people to change their behavior all at once. And, to produce the standard Drugar quality, a farmer needs to invest relatively little of their time because they can strip-pick, dry the coffee on the dirt right in front of their house, and sell it to the buyer who comes to their shamba to carry it away.

Natural-processed coffee is traded in kiboko (or dried cherry) form, and to be honest, once it’s dried down, it’s really hard to tell what the starting quality was: under-ripe, over-ripe, or whatever it all becomes brown. So, it’s really hard to keep any good quality naturals segregated completely from this Drugar business.

What BJCU decided to do was to change the whole system and begin washing coffee in Western Uganda--which I think they were the first or among the first to do there. They mobilized communities to build these washing stations and really focused on educating their members about quality, which we talk about in an earlier post. The cooperative got control of the processing from the cherry onward so it could be standardized and farmers now get paid at the point that they deliver their cherry, so the incremental increase in their work is around selective picking and transportation. But, the price they are getting from the quality increase and the certifications is significantly higher, so it’s enough of a motivator to encourage participation. They can also still take their un-ripes, floaters, and other lower grade stuff home to dry and sell into the Drugar market.

So really, just changing from Natural to Washed has been the quantum leap in quality. As you would expect, there have been a few hitches along the way as BJCU really built this from the ground up. As one example, I think it was the first or second year, we told them to grade the coffee into different screen sizes, which they did. So far so good, but then they put all the coffee into identically labeled bags, so we would open one and find 15 screens and then next bag would be 18 screens, which turned out to be a fun roasting challenge for the buyers!

Drew: What do you see as unique strengths and exciting possibilities for the specialty coffee from this region?

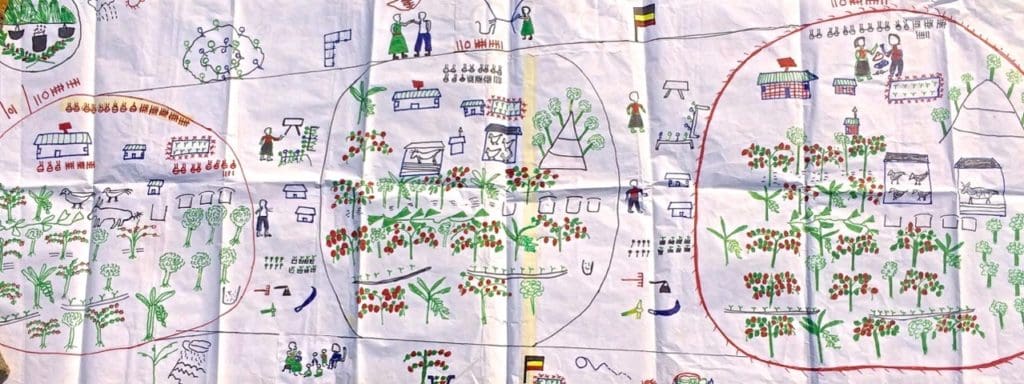

Jen: To me, their strength is really in the cooperative’s operational model. We talk about the GALS program also in this earlier post and over on the main BJCU page, but it’s worth repeating. This methodology involves members of the cooperative all the way from individual household planning and goal setting all the way up to the larger cooperatives’ goals and initiatives. You can really see the buy-in, in everything from quality compliance at the washing stations to the disbursement of Fair Trade premiums. I also feel that they are all so eager to learn and improve, so every season they implement some new system or process that helps to improve quality. A lot of that is based on direct feedback from their buyers so it’s a great feedback system.

Drew: When it comes to quality outcomes for the Bukonzo Joint coffees, much of the success is reliant on the work of the individual washing stations. Can you tell us a little bit about how they are structured, run, and equipped? What are some of the challenges they face?

Jen: The washing stations are organized and run cooperatively, so they have various board members much like the larger Bukonzo Joint Cooperative. Members take turns staffing the washing station, so you will have a Monday team and a Tuesday team of farmers who come and do the weighing or run the pulper and all the other jobs in the season.

The equipment is pretty basic. Each station has a scale, obviously, and either a hand-cranked pulper or in some cases a generator and a Penagos Eco-Pulper. All of the fermenting is done in buckets. Then, because the harvest happens during the rainy season, all of the drying is done in drying sheds in these tiered racks. Wet coffee starts on the bottom and gets moved up once it is dry enough not to drip.

Usually the washing station is on a coop member's land, and that member gets rent for the space. Because the farmers need to keep as much of their land in food or cash crops as possible, you can imagine it’s hard to get a lot of space. So, space is really at a premium and this can be an issue if the harvest comes in faster than usual.